Organization Homes and Improvisation

“America in Crisis” Charles Harbutt, Saatchi Gallery, London, 2022

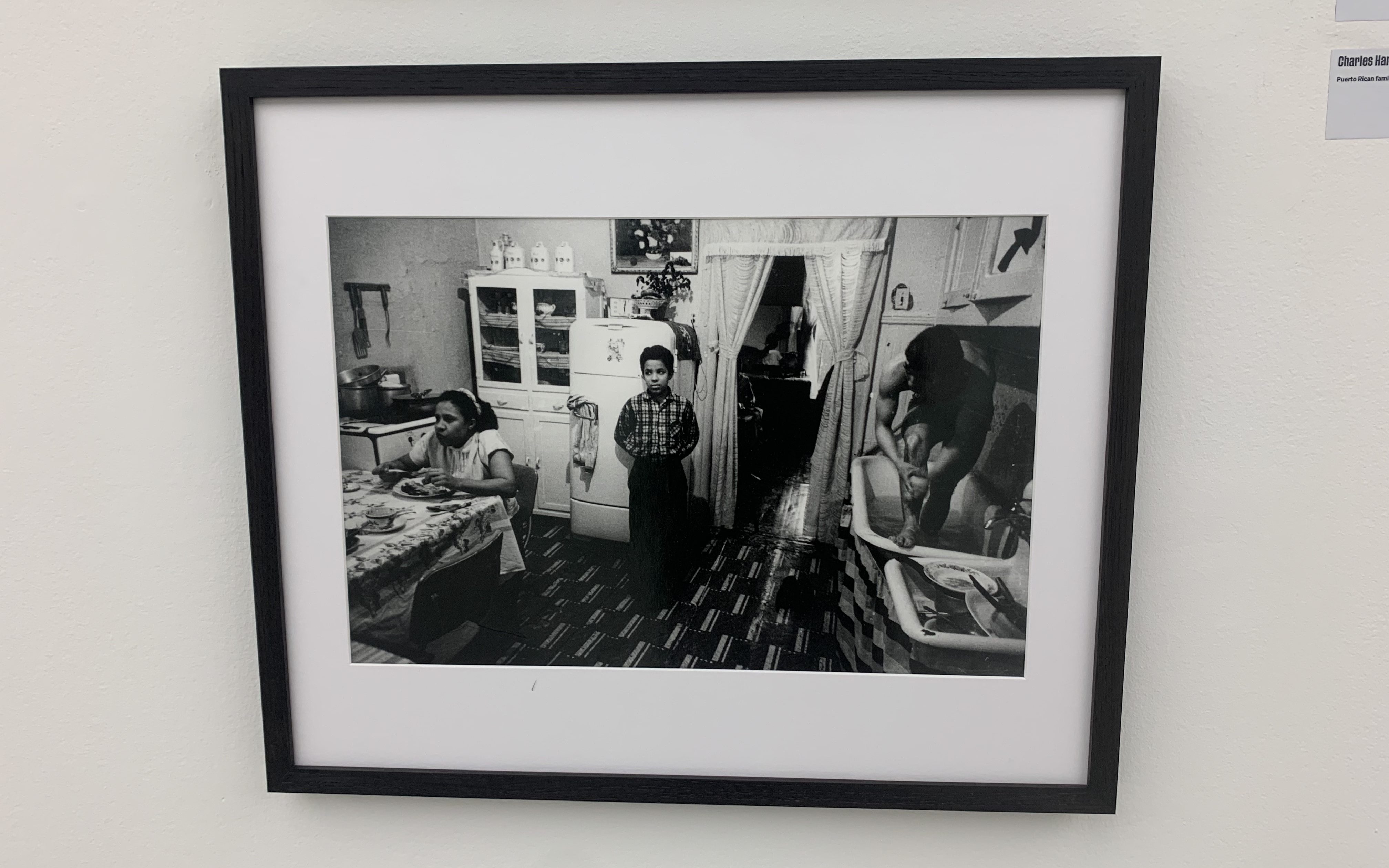

We start this series from one image in the Saatchi Gallery’s “America in Crisis” exhibit in 2021 that always stuck with me. Charles Harbutt captures a Puerto Rican family in a New York City tenement, with a jarring mix of three people doing chaotic differently things in one enclosed, seemingly tight kitchen. Harbutt captures this in motion, as if us, the viewer is offered a beautiful and unique glimpse of a snapshot of a family life. For this, I feel a deep sense of vulnerability and intimacy.

Upon further retrospection, I ask myself, why Harbutt, a photographer that always has multiple frames, would choose this one seemingly insignificant moment to display in an art gallery. Surely, there is a logic that under-pins the woman eating a meal, the child in waiting and the man bathing in the wash basin. For me, that logic is the display of improvisation. The needed improvisation of recent immigrants bathing in the sink in the kitchen mirrors the larger need to co-exist, adapt, and conduct daily life amidst the difficulties that surrounds one’s existence.

Ever elusive and moving, how do, or even, can we capture improvisation? After all, it is not often that we are given access to the deep emotional candor of how people make difficult choices. At the same time, from the clothes we wear to the people we prioritize, improvisations precede our every day existence, and are felt far more unequally for some than others.

_____

I always felt like I grew up with the love of many mothers.

Maybe this is a dramatic statement, but I remember my entire childhood life with the presence of extra live-in carers, individuals who rarely occupied a central frame, but without whom I would not be sitting here in these high ivory towers slowly and iteratively reflecting on my past.

On Sundays in Hong Kong, my parents would have my grandparents and extended family members for dinner. In a 800 square feet apartment, (which was large for Hong Kong standards) hosted 9 people, with rowdy kids of my cousins, my brother and myself running around.

It does not take much imagination to picture the chaos.

Nonetheless, it was this one tradition that my family held, the one dinner that even my Dad, then often spending weeks in Amsterdam or Paris, would be a constant attendant. The image of us, sitting by the extendable table, with a colorful mix of every chair in that apartment, reminds most of my teenage years and of my grandfather. There are many photos from this period, yet few contain one resounding figure, Ella, who always took the photos rather be in them, always flanking my childhood years in Hong Kong.

Ella, our live-in domestic carer, moved from Indramayu, Indonesia to Hong Kong in her early twenties and lived with us for the 8 year period in North Point. Ella spent much of those years parenting for me and my brother. She would pick me up from the school bus, often when I was aloofly motion sick, go grocery shopping in the humid summers, and cared for me when I was sick. Our needs were almost always placed before her own. I always remembered Ella’s kind-hearted and enthusiastic strength to the world.

When I reflect back on this period of my life, it is hard to not feel an undercurrent of guilt. Of what right, did I have the privilege of her care? Of her, granting us both her emotional and physical labor at such an equally important juncture of her life? I don’t have the answers to these questions, and I likely will grapple with them for a while. What I have tried to do is to retrace the steps and frames of her independent life, and less in relation to my family.

BCA Organization Home, Causeway Bay, 2022

Every Sunday, Ella would spend her day in an “organization home”, a place that gives membership to migrant workers and is a collective gathering space on vacation days. The photos above are the location of the home in the busy streets of Causeway Bay, along with the organization’s storefront selling cute Indonesian pastries.

I imagine what she felt in those Sundays.

Did it feel liberating to be able to converse in her home language, to cook with her friends without worrying if dishes contained pork? Did it give her a sense of belonging in a city that so ostracized and other-ed migrant workers?

I really do hope so.

From what I remember, she would always seem excited to head off to her space, and would be happier afterwards. In this way, organization homes feel like true bastions of improvisation when the city fails to provide; a nexus of cultural capital, mutual assistance and crucially, a space of belonging and familiarity.

Ella’s story is one of many, of the hundred of thousands of migrant workers that have given their labor to this city that seldom looks around to be thankful. I last saw Ella when was 14, and I know my parents always treated her well- compensating her above the required salary, paying in full for her surgery back home and more. Yet, it is hard for me to sit here and argue that better implies sufficient.

To be honest, it is still an uneasy history for me to recognize, to reconcile with a childhood that is simultaneously nostalgic yet fraught. I suppose this is the responsibility we all hold, as beneficiaries of an exploitative system. Admittedly, it feels conceited to sit here and reflect, implying that these words somehow mend the broken structures that underpin Hong Kong.

We must not lie to ourselves to self-gratify.

But for me, it is an attempt at introspective honesty- to gradually recenter Ella in the frames of my upbringing and bring a much missing and under-appreciated foreground of her daily improvisations. I hope she is doing well.

Ella Sari Elassari, Hong Kong Airport, 2015

_______

For those who are curious, Nicole Constable’s “Maid to Order in Hong Kong” is an ethnography that features the emotional labor and power of migrant workers during the Asian Financial Crisis and SARs epidemic.